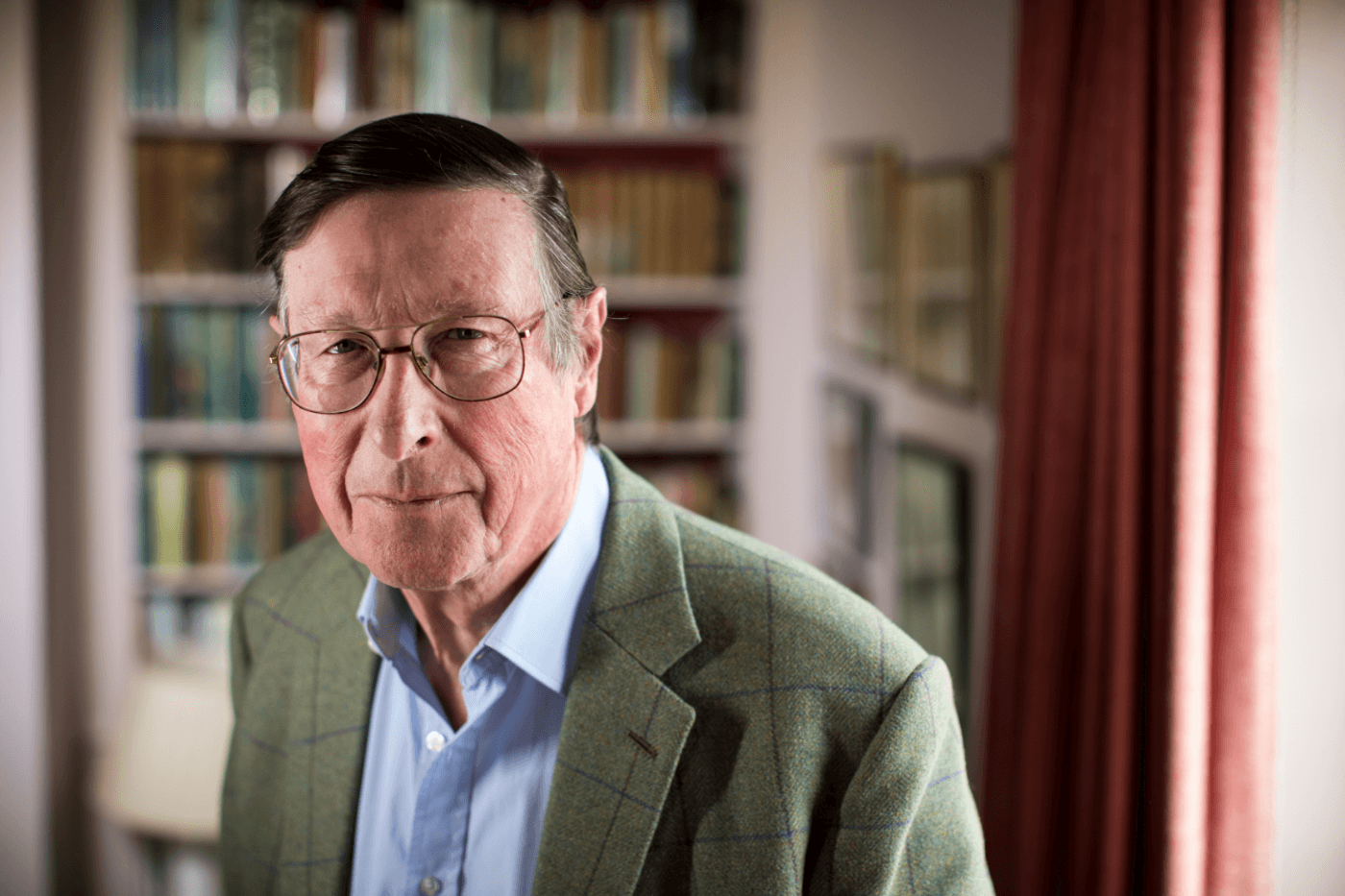

Below is Max’s tribute to Britain’s foremost historian, Professor Sir Michael Howard OM, CH, MC, FBA, which he delivered on 25 February 2020 at a memorial service held at King’s College, London, following Sir Michael’s death on 29 November.

I first met Michael half a century ago, as a friend of my parents. He became to me, as to countless other aspiring writers and historians, a mentor and counsellor. We embraced his wit, intellect and kindness, while remaining wary of the warmth of his temper. Punctilious courtesy did nothing to diminish the strength of his opinions about matters he deemed important. At Oxford I once solicited his support for a friend, a popular historian, who coveted the Chichele professorship. Michael dismissed his pretensions in a withering sentence: ‘can you imagine him supervising post-graduate theses?’. On another occasion I pleaded for mercy towards a notoriously bibulous don, facing expulsion from the university. I suggested that this clever rake added to the gaiety of nations. Michael responded fiercely: ‘you would take a less indulgent view if your daughter was being tutored by him. I have not encountered that brand of giggling, drunken mischief-making since Guy Burgess!’.

Thus, in the portrait of Michael’s greatness- and greatness it was- we should acknowledge that a portion of it was to set the highest intellectual and ethical standards, and to disdain some who fell short of them. Although he cherished lifelong liberal views, not long ago he told me how shocked he was, in his early years at King’s, by the impenitent Stalinism of Ralph Miliband, then teaching down the road at LSE. Never for a moment did Michael’s conviction falter, that the West represented the right side in the Cold War. In the post-Soviet world, I asked him in a TV interview, whether the Russians might become our friends. Unlikely, he responded: ‘They will always be envious of our success, resentful of their own failure’.

During the last 20 years, scarcely a week passed in which I did not see him, or at least exchange words. He was as elegant and measured a conversationalist as writer and lecturer. He never knew the names of my children, because nugatory domestic matters did not engage him. Rather, and especially as he became confined to Eastbury where he presided over that wonderful galleried library, he cherished an insatiable appetite for discussion of big things, big books, the state of the world. Since we were both deaf, and thus shouted at each other, local pub regulars said they knew with embarrassing exactitude what he thought of President Trump, the Royal Navy’s aircraft-carriers, gays in the front line and the forsaken art of diplomacy. Every occupant of the bar knew that Michael thought it rash for a state to found its entire strategy, as does Israel, upon an assumption of perpetual military superiority. Local racing buffs were made aware that he thought the only thing worse than Iran’s acquisition of nuclear weapons would be a Western resort to war to prevent this.

He told me many things that I think he wanted somebody to know, after he was gone. For instance, one day a year ago he asked: ‘have I ever told you about my only girlfriend?’. No, he had not. He described how, after the war, he became close to Anne Balfour, daughter of a grand Scottish family, at whose stately home he stayed, making his only foray into grouse-shooting. Eventually they decided that a sexual relationship would suit neither. She was briefly married to that razor-sharp Grenadier officer David Fraser, and thereafter became a distinguished documentary film-maker. Anne and Michael remained close until her death three years ago. Though women as a sex played no significant part in his life, there always remained a place in his heart for clever ones.

I once mentioned that we had seen David Hare’s play A Moderate Soprano, about Audrey Mildmay and the beginnings of Glyndebourne. Michael said that while his father never kissed him, ‘he was very good about things like taking me to music’. At Glyndebourne’s second season, he heard Mildmay sing. How was she, I asked? He replied dryly: ‘a moderate soprano’. He was a child of a rich, self-consciously cultured, cosmopolitan, upper-middle-class tribe that is now gone with the wind. He retained a devotion to his extended family, and long ago stipulated that his ashes should be interred, as they were last month, at his parents’ old Dorset country home. For years, he was a regular attender at his local Anglican church, the rituals and music of which he loved, but latterly he became fascinated by the German Jewish identity of his mother.

Michael was unswervingly rigorous in his judgements, about both past and current events. He tutored me about the limitations of the wartime British Army: ‘it cannot too often be stated: they’- the Germans- ‘were better than we were. We battered our way to victory with a maximum of firepower, a minimum of finesse’. Only a few months ago, he lamented the impact on the British psyche of victory in the 1982 South Atlantic war: ‘After Suez we had gradually come to terms with our much diminished importance in the world. Then along came the Falklands, to revive all the absurd old national delusions’. He displayed an impressive willingness to change his mind. When first he told me of his opposition to replacing Trident, I expressed surprise, because he had long been a staunch advocate of Britain’s deterrent. He replied: ‘when circumstances alter, so do I. We are no longer rich nor significant enough to own such a weapons system’.

After 9/11, he was among the first to denounce President Bush’s excesses, asserting that one could no more have a war on terror than a war on wickedness. He deplored national leaders’ rhetoric, endorsing the bromide of peace, when the proper objectives of every foreign policy are order and stability. ‘The great lesson of my lifetime’, he said, ‘is that all difficult problems must be addressed with partners and allies’. He became increasingly despairing about the enthusiasm of governments and indeed electorates on both sides of the Atlantic to dismember the global systems which he himself had made a significant contribution to creating, together with the attempted renunciation of the Enlightenment commitment to reach conclusions and decisions on the basis of a rational examination of evidence. He observed bleakly, in the context of 21st century trends, that while communism was always an ideology of elites, fascism was popular. He recited from memory Auden’s 1937 poem Dance of Death, especially the lines: ‘It’s farewell to the drawing room’s civilized cry, the professor’s sensible whereto and why, the frock-coated diplomat’s aplomb. For the devil has broken parole and arisen, he has dynamited his way out of prison’. His other favourite party piece was a recitation of Noel Coward’s There Are Bad Times Just Around The Corner.

Michael believed that climate change will drive a shift of peoples from the southern to the northern hemispheres ‘which represents the most significant and dangerous shift of populations since the early Christian era’. Despite a wonderful sense of fun and addiction to the works of Agatha Christie, he was a profoundly serious person. When I suggested that the old have a duty to forswear the propagation of gloom, he replied tartly: ‘I am not in the habit of quoting Italian Marxists, but I give you Gramsci’s line: we must have optimism of the spirit, pessimism of the intellect!’. I shall not fracture the harmony of such a gathering as this one, by rehearsing his views on the recent governance of Britain.

In his nineties, Michael was obliged to abandon attendance at the institutions he loved: All Souls, the IISS, Literary Society, Garrick and Athenaeum. He continued to read and reread prodigiously; grieved that deafness closed his ears to music; still delighted in the company of intelligent soldiers. He was a man full of passion, above all for his beloved partner for over half a century Mark James, who accompanied him on so many journeys; brought so much laughter, insight and wit into both their lives; ran their cottages and garden with love and enthusiasm. Mark outlived Michael by barely two months. Medical science says that motor neurone disease killed him; most of us think that, in truth, he died of a broken heart. They are now at peace and together once more, in a place where dear Mark should no longer have to do the cooking.

Michael’s foremost consolation in infirmity was that he knew what his life had been. His considerable vanity was a just vanity, about the righteous causes he had espoused, the generations of students and warriors he had influenced. My wife Penny often said, after Michael left our house: ‘it has been a privilege to know him’, and of course she was right. In hospital a couple of days before his death, through a haze of morphine he said beatifically: ‘I’ve been terrific, haven’t I?’. His niece Clare and I prayed that this wonderful repository of human wisdom heard us respond, on behalf of all his host of friends and disciples: ‘yes, dearest Michael, indeed you have’.